The current ice age began some 2.6 million years ago. The assertion that we are now in the grip of an ice age might surprise you, but that's because ice ages comprise a series of cycles of glaciation and warmer inter-glacials, and we're in the midst of one such inter-glacial now. Further, we use the term 'ice age' carelessly for the glaciations within the overall ice age, hence the confusion. For the first one and a half million million years of the ice age the cycle was about 40,000 years; since then however the cycle has stretched, so that we've fairly reliably experienced a pattern of some 20,000 years of relatively balmy inter-glacial followed by 80-100,000 years of cold, dry, windy glaciation.

The most recent glaciation had its major impact in Australia from about 35,000 years ago, ending only about 13,000 ago. But what's this got to do with Tasmanian birds? Fair question, and the answer is 'just about everything'. During glaciation a large amount of the earth's water is locked up in ice sheets, especially at the poles. Sea levels drop and large expanses of continental shelf are exposed - that is, the shore lines are much further out relative to modern ones. In particular currently major islands, including Tasmania and New Guinea, were simply highland areas across grassy plains where Bass Strait and Torres Strait now surge.

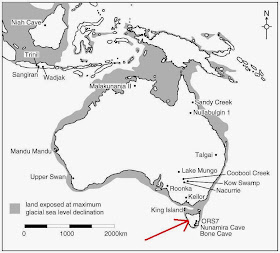

|

| The shadings represent dry land at the height of the last glaciation; I've indicated Tasmania with the red arrow for those unfamiliar with Australian geography. Map courtesy of Peter Brown. |

So, for those 20,000 years animals (including humans and birds) could move freely between what is now Tasmania and the mainland. Moreover it is likely that this was also true (albeit not for humans) for at least some of the other nine glaciations in the last million years, though the most recent one seems to have been particularly intense.

On the other hand, the cold treeless steppe-lands of the Bassian Plain (now Bass Strait) would have been highly unattractive to forest birds, so for them the plain may have been as effective an isolator as the current 200km of stormy sea. All this means that the evolution of the twelve species of birds endemic to Tasmania need not have occurred in the last 13,000 years, and indeed is unlikely to have done so, particularly for one which is in its own genus.

OK, enough background - let's just meet a few of those birds, along with their nearest mainland relations with whom they share a common ancestor.

Perhaps the first you are likely to meet - and the one you're probably going to see most regularly in the east - is the wonderful Tasmanian Native-hen, one of only two flightless rails in Australia. It is no coincidence that the other is also an islander, the Lord Howe Island Woodhen. It is also no coincidence that, while the Tasmanian hens are known from mainland fossil deposits, they abruptly disappeared at the time the Dingo arrived, some 4700 years ago. There can be no smoking gun, but a flightless bird would have been hugely vulnerable to such a quick clever hunter. Further, it's most unlikely that a smallish flightless bird would have evolved on the mainland, so I suggest they arose in Tasmania, and 'crossed over' during the last glaciation; unlike all the other endemics, they're not forest birds.

|

| Black-tailed Native-hens Tribonyx ventralis (and Great Egret) Kinchega National Park, western New South Wales. Found right across arid Australia, and the only other member of the genus. |

Green Rosellas Playtcercus caledonicus are clearly closely related to the mainland Crimson Rosella P. elegans, though are not as abundant or quite as cooperative for the most part.

|

| Green Rosella, Bruny Island. |

|

| The resemblance is most striking to the immature Crimson Rosella (adults are indeed crimson). |

Another loud and proud Tasmanian is the world's biggest honeyeater, the huge and raucous Yellow Wattlebird Anthochaera paradoxa. As with the closely related mainland Red Wattlebird, the name refers to the colour of the facial wattles, a source of endless confusion.

|

| Yellow Wattlebird with cicada snack, Bridport, northern Tasmania. |

|

| Red Wattlebird, Canberra. |

Another with very obvious mainland connections is the big noisy Black Currawong Strepera fuliginosa. Oddly though, in high-use national park areas where it was abundant and decidedly pushy when I was last there 13 years ago, and where the literature claims it still is, it was virtually non-existent. Not so in the forests south of Hobart however.

|

| Black Currawong, Tahune Forest. |

Of the smaller endemics, undoubtedly the most abundant in shrubby understorey from rainforest to coastal scrubs is the rather plain Tasmanian Scrubwren Sericornis humilis. There is some disagreement as to whether it is indeed a separate species from the equally abundant mainland White-browed Scrubwren S. frontalis, but the current general consensus is that it is.

|

| Tasmanian Scrubwren, Freycinet National Park, east coast. |

|

| White-browed Scrubwren, National Botanic Gardens, Canberra. Her leg adornments are due to the fact that she lives over the road from the Australian National University Zoology Department. |

Another in the scrubwren family, with no close relations (the only one in its genus) is presumably the product of an earlier period of Tasmanian isolation. The active little Scrubtit Acanthornis magna is a busy and inconspicuous insect hunter of rainforests in particular, often overlooked I suspect.

|

| Scrubtit, Liffey Falls, west of Launceston. |

There are three small endemic honeyeaters, two of them in the genus Melithreptus, short-billed honeyeaters which primarily glean insects from leaves rather than rely on nectar. The Strong-billed Honeyeater M. validirostris is, in my experience, the least common of the three, but is the only one I managed to photograph. The other two are the smaller Black-headed Honeyeater M. affinis and the Yellow-throated Honeyeater Lichenostomus flavicollis, both of which I found impossible to entice to stop still for more than a millisecond!

|

| Strong-billed Honeyeater (immature) Wielangta Forest, south-east Tasmania. |

|

| The mainland Brown-headed Honeyeater M. brevirostris (here near Canberra) seems to be its closest relative. |

The other Tasmanian endemics are the Dusky Robin Melanodryas vittata, the Tasmanian Thornbill Acanthiza ewingii (of which my only picture is too fuzzy to inflict on you) and the rare Forty-spotted Pardalote Pardalotus quadragintus. I hope you track them all down when you next go to Tassie - it's not that hard - but meantime I think that having some understanding of how they came to be is interesting in its own right.

I'll pursue this theme with Western Australian endemics at some time in the future; and I've now made lists of all the topics I've promised to pursue 'at a later date'!

BACK ON TUESDAY

No comments:

Post a Comment