Not too long ago I did a 2-part post on the delights of the upper Blue Mountains, based on stays in summer and spring in the admirable Rough Track Cabins just outside of Blackheath in the upper Blue Mountains. We have just returned from our first Autumn visit there, and things are different enough to warrant a further post on what's happening now. I've made sure that I'm not repeating the same scenes or species, so to get the setting if you're not familiar with it you may wish to look at the previous posts.

The weather was clear and sunny throughout our stay, not something we can presume in this part of the world, and we visited a series of the famed lookouts over the dramatic sandstone scenery, including some we'd not previously seen. Here are a few of our favourites, starting with the iconic 'Three Sisters' at Katoomba, albeit from a different angle from that usually featured.

Here are three panoramic views from different lookouts, but all of which look east across the mighty Grose Valley.

|

| From Govett's Leap; he didn't jump, the term is from Scots lowp or loup, which does refer to a jump, but in this case (and others in the Blue Mountains) means a waterfall. |

|

| From Victoria Falls Lookout (though in fact the falls are quite a walk from here). As you may have divined, I love sandstone, for its formations and for the rich vegetation it supports. |

This one however looks south from Katoomba Falls Lookout into the Jamison Valley; the Kedumba River, which tumbles over the Katoomba Falls, joins with the Jamison River far below.

|

| Looking across to the falls... |

|

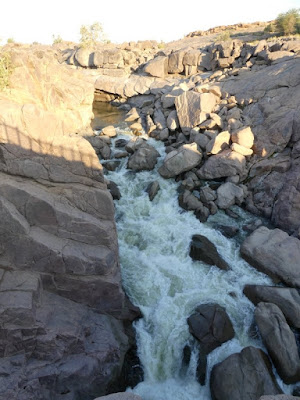

| ... and from below. There are lots of such unfortunate names in the mountains, dating I suspect from early tourism campaigns. |

|

| There are two segments to the falls which, despite good tracks and proximity to the main Katoomba tourist drag, is often overlooked by visitors. |

The forests below the cliffs contain pockets of Warm Temperate Rainforest, dominated by Coachwood Ceratopetalum apetalum and Sassafras Doryphora sassafras.

|

| Temperate rainforest by Witch's Leap Falls. Some of this rainforest also contains eucalypts, especially Brown Barrel Eucalyptus fastigata. |

|

| Old Brown Barrel among Coachwood. |

A favourite Blue Mountains rainforest walk of ours is at Coachwood Glen, at the head of the Megalong Valley. I introduced it last time, but any bushwalk is different every time. Also this time, because it's autumn, there were lots of lovely fungi, but we'll meet them soon. A couple of scene-setting shots of the glen.

|

| Old Coachwood roots growing over a mossy boulder. |

|

| Vines on Coachwood. |

|

| Below Witch's Leap Falls; Rough Tree Fern Cyathea australis in foreground. |

|

| Tender Brake Fern Pteris tremula covering the forest floor at Coachwood Glen. |

| |

Sunset on the track to Rough Track cabins; the dominant tree here is Sydney Peppermint Eucalyptus piperita. |

|

| Silvertop Ash Eucalyptus sieberi growing along the ridge of Narrow Neck Plateau which separates the Megalong and Jamison Valleys. |

|

| Scribbly Gum E. sclerophylla woodand, Megalong Valley. |

|

| These Scribbly Gums really are beautiful trees; this one was growing out of sandstone at Perry's Lookdown. |

|

| Blue Mountains Mallee Ash E. stricta, in heathy forest near our cabin. |

|

| Blue Mountains Ash E. oreades is found in moister situations. |

|

| Regenerating burnt forest in the Grose Valley, from Victoria Falls Lookout. |

|

| Burnt banksia cones, Narrow Neck Plateau. The seeds dropped into the ash bed a couple of days after the fire, when the ground had cooled, to start the regeneration cycle |

Last spring there was major flowering in the burnt areas, and it continued through summer when we couldn't get there because of COVID in Sydney (for quarantine purposes the Blue Mountains were regarded as part of the Greater Sydney Area). Some was still evident even in April however.

|

| Flannel Flowers Actinotus helianthi in burnt heathland at Perry's Lookdown. This beautiful sandstone plant flowers occasionally in autumn but we found it quite regularly in the burnt areas. |

|

| I found uncountable dried plants that had finished flowering on the bare exposed Narrow Neck ridge line, but no fresh flowers.... |

|

| 'Delighted' doesn't cover my emotions at this find, one I'd never thought to see. |

|

| Heath Banksia B. ericifolia. Like all banksias the flower spike comprises hundreds of small flowers, many of which are pollinated by small mammals. |

|

| Silver Banksia B. marginata. |

|

| Hairpin Banksia B. spinulosa. |

|

| Platysace lanceolata, another summer-autumn flowerer. |

|

| Coral Toothed Fungus Hericium coralloides growing on a dead section of trunk of a Coachwood. |

|

| Turkey Tails Microporus affinis, a bracket fungus, growing on a fallen Coachwood branch. |

|

| Bonnets Mycena sp. forming a tiny moss garden on a fallen tree trunk. |

|

| Golden Scalycaps Pholiota aurivella growing out of a crevice in a Sassafras. |

|

| Ruby Bonnet Cruentomycena viscidocruenta, a tiny little gem growing in very low light. |

|

| Sydney Mountain Darner Austroaeschna obscura resting on the path to Perry's Lookdown. My thanks to Harvey Perkins for the id. |

And remember that you can get a reminder when the next post appears by putting your email address in the Follow by Email box in the top right of this screen.

I'd love to receive your comments - it's easy and you don't need to sign in!

no control over it. I keep hearing of people who are no longer getting

notifications of new postings and I'm losing readership presumably as a result.

You might like to set a calendar alert as a back-up to avoid missing out.

Alternatively, if you'd like to send me an email (to calochilus51@internode.on.net)

I can put together a mailing list to send out whenever a post goes up;

I guarantee never to use your address for any other purpose.

Thank you!