As my more assiduous readers may recall - and I understand that there are a few of those! - in 2019, not long before COVID profoundly altered travel, we made a very special trip to East and South Africa to celebrate a new stage in our life. We were guided (excellently) in Kenya and Tanzania but hired a car and did our own thing in western South Africa. I've reported on aspects of the odyssey here of course, but today I want to share with you three much more modest little reserves in the arid north-west of South Africa. As suggested in the title, we had very little time in each of them and they all deserved more, but even those brief visits were memorable. Maybe more time, another time?

This country is arid, with dunes to the east and vast piles of tumbled granites to the west. Some of it reminds me strongly of parts of inland Australia. We loved it, but were restricted by time and by our little 2WD hire car. Here are three little reserves, two of which were quite unexpected, in which we spent a total of just two nights and all of which we'd happily return to for longer.

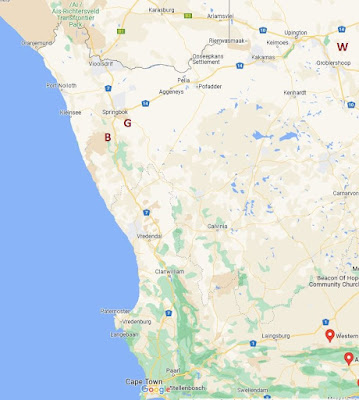

|

| From east to west (the order in which we visited them) W = Witsand Nature Reserve, G = Geogap Nature Reserve, B = Brandrivier private reserve and farm. |

|

| As the name suggests, this is a sandy landcape, dominated by hardy arid-adapted plants, and especially by Camelthorn Vachellia (fomerly Acacia) erioloba. |

|

| Sunset, above and below; in my opinion nowhere does sunsets quite like the deserts. |

|

| Early morning view from the dunes, across the white sands which give the reserve its name to the distant red sands of the Kalahari Desert. |

|

| Familiar Chats Oenanthe familiaris are indeed familiar around dwellings, chasing insects and generally ignoring us. This one was no exception. |

|

| Kalahari Scrub Robin Cercotricha paena, a flycatcher unrelated to either Old World or Australian robins. |

|

| Cape Glossy Starlings Lamprotornis nitens are widespread and common but nonetheless stunners, and we never tired of them. This one caught the morning sun beautifully. |

|

| Unfortunately I was unable to lay lens on the ever-busy Dusky Sunbird Cinnyris fuscus which was feeding on the mistletoe, but the flowering plant is worth admiring in its own right. |

|

| Scrub Hares Lepus saxatilis are restricted to southern Africa |

|

| Steenboks Raphicerus campestris are more widespread, extending to East Africa. They are a small antelope, standing no more than 60cm high. By now the light had almost gone! |

|

| The White-browed Sparrow Weaver Plocepasser mahali is a handsome weaver which, like other weavers, nests colonially (but, unlike the Sociable Weaver, in separate nests). |

|

| Namaqua Sandgrouse Pterocles namaqua. I'm a big fan of the desert-loving sandgrouse, and these gorgeously patterned birds were a delight. |

Spring in Namaqualand is famous for its flowers, but we were there in June - and in drought. Some aloes provided colour though.

|

| Typical Goegap landscape - it's always dry of course, but not this dry. |

|

| I'm not sure of the identity of this aloe, but it looked magnficent among the Goegap rocks. |

The real highlights however were both mammals. Just after we entered the reserve a couple of little heads appeared above a bush in an especially open sandy area; I assumed they were spurfowl but then, to our delight, three Meerkats Suricata suricatta burst into a gallop across the sand with tails in the air and vanished into a culvert under the road. They were the only ones we saw for the trip and we were thrilled.

The walls are canvas, but you wouldn't call it a tent! It is set high above the highway which goes through the pass below. You can hear trucks sometimes, but they feel pretty remote. The magnificent verandah looks out over the valley one way, and up into the rocky hill behind. There's an excellent gas barbeque on the verandah and an outside shower among the rocks (plus a good indoor bathroom). Solar panels provide lights and there's a fridge. It certainly warranted more than a one-night stay!

|

| View of the rocks behind (and the barbeque). |

|

| This one fooled me for a while, until I discovered that the Mountain Wheatear Myrmecocichla monticola, which I know as a black and white bird, also comes in grey! |

|

| This is the lovely flower of the shrub above. I assume that it's in the Mytaceae family, but beyond that I have idea - any assistance welcomed! |

|

| This little chap came out to clean up the barbeque even before it cooled, and before I had a chance to do so. I'm pretty sure it's not a House Mouse, but I don't what the options are there. |

So, three very different little reserves, each a treasure. This is one occasion when I'd be a bit surprised (pleasantly of course!) if anyone reading this has visited any of these reserves. If I'm wrong please let me know of your experience there. Otherwise, if you get the chance to visit any or all of them, try and give yourself more time in each of them than we did on this occasion - they, and you, richly deserve it.

NEXT POSTING THURSDAY 26 MAY

Should you wish to be added to it, just send me an email at calochilus51@internode.on.net. You can ask to be removed from the list at any time,or could simply mark an email as Spam, so you won't see future ones.